Hidden deep within the imagination is an often-unacknowledged longing for a utopia. Each person’s visualization of that place would be different, but common to many would be a desire to live in physical and emotional harmony in a place of abundance and beauty. We might dream of a utopia, an imaginary place that literally means ‘nowhere’ or ‘no-place’, but in central Australia, held in a precarious balance, Utopia exists. An extraordinary beauty emanates from the traditional Aboriginal people’s harsh, uncompromising land and art, yet this Utopia is a very real and complex place with no room for sentimentality, a place where life is difficult and extreme. Nothing is taken for granted. Conditions are much like that of a third-world country with little to no infrastructure, and health statistics are grim and heart rending. There are far too many early deaths. For an ancient oral culture, the loss of elders is not only tragic, but means a loss of wisdom and experience.

Utopia is a remote Aboriginal community about 240-kilometres northeast of Alice Springs on approximately 5000-square miles of land. Permits are required for non-indigenous people to visit, and these are rarely granted. A shifting population of about two thousand Anmatyerre and Alyawarre people live in extended family groups on sixteen outstations. Their ancestors have lived here for tens of thousands of years and called it Ankerrapw, a name that comes from the words ankerr for emu and apwa for emu feathers.

A few of the Aboriginal elders of Utopia still remember the first white man they saw. For the Petyarre sisters, this was an ominous vision, for it was their father who in 1927 showed compassion for two white brothers and took them to a reliable water soakage. The brothers then chased him and his family off their homeland and sacred sites to use the land area for grazing sheep. They established a pastoral station and named it Utopia for its abundance of rabbits, a familiar European meat source greatly welcome to them but an introduced species that has caused untold environmental damage in Australia.

Nearly fifty years later, Stolen Generation artist Barbara Weir, daughter of Minnie Pwerle, an Alyawarre woman, was amongst a group of Utopia people instrumental in fighting for Land Rights in 1976. It became the first successful Land Rights claim of a pastoral station in 1981. Yet by then, jobs that Aboriginal men held as stockmen on pastoral stations had virtually ceased. Today, there is basically no other employment in this remote place other than that of making art. Utopia men and women, young and old, now paint vibrant acrylic paintings of their ancient Dreamings, many of which hang in galleries and museums throughout the world.

When I first arrived in Australia as an artist from England at the end of 1993 I was immediately drawn to paintings by Emily Kngwarreye, and I sought out her powerful, beautiful artworks wherever I could find them. Through a chance meeting with her niece, Barbara Weir, I was fortunate to discover many of the complex and interwoven stories that lie beneath the surface of Utopia artists’ remarkable paintings. The artworks are a contemporary hybrid of an ancient culture that has used visual gestures and mineral ochre pigments for thousands of years in body painting and sand painting. Aboriginal art is first and foremost the artists’ declarations of their relationship to their homelands which they call ‘country’. Their mythic Dreaming stories map the journeys of Dreamtime Ancestors who created the landforms and topography of Utopia, and its plants, and animals. Elaborate kinship systems establish the people’s roles as custodians of their country. Past, present, and future are experienced as an ever-present integrated reality where sacred and secular are not separate. Dreamtime stories are told, sung, and danced in traditional men and women’s ceremonies that are still very much alive at Utopia. A person’s main Dreaming is based on aspects of the specific land for which they are custodians, and is passed down in a paternal lineage. The women depict in their acrylic paintings non-secret/sacred aspects of their father’s and grandfather’s Dreamings, as well as their mother’s Dreamings that come from the place of their conception.

Women play an essential role in the continuity of the culture as important providers, hunting small game, gathering and preparing plants for cooking and medicines, looking after children and being responsible for the women’s ceremonies called awelye. Teaching occurs naturally and continually as new generations are taught ancient traditions. Respected female elders like the late Emily Kngwarreye teach survival skills as well as ritual body painting, songs, and dances to young girls in ceremonies that last for many days and nights. The women dance and sing to maintain their connections to their country, for the increase of plants and animals, for happiness and success in love, and for health and well-being in the community.

Amongst this continuity of culture, there are poignant examples of survival and resilience in the face of the tragedies and discontinuities forced upon it. One inspirational story of hope and courage is that of two immensely talented artists, the late Minnie Pwerle who was born around 1910 and her daughter Barbara Weir. I met Barbara in 1998 and she asked me if I would record her stories, many of which had been too painful for her to tell before. Over the years she took me to Utopia with her and introduced me to her family and country. The process of being a friend and witness to her stories was a great privilege, and hopefully provided some small amount of healing for her.

Barbara was ‘stolen’ by a government official because her father was a white man while she was out collecting water for her Auntie Emily Kngwarreye when she was a young girl at Utopia. This is her story in her own words:

"I was born around 1945 and I came from two people. I was born at Bundy River Station, near to Utopia. My mother’s country is Atnwengerrp, her language is Alyawarre. My grandmother was Anmatyerre, her father was Alyawarre. My dad, Jack Weir, was an Irishman. He married the station owner’s daughter. I was taken away, I guess around 1957, when Dad was taken to jail for going with my Mum. Early one morning, I went to get water with a billycan with Glory Ngale. We saw a Land Rover and we went behind a tank but he [a government official] grabbed me and took me to my mother and made her make a cross to sign [her consent]. There was sorry business [mourning rituals] ‘cause my family thought they’d kill me… My mother had to forget about me…I was like a ghost when I went back in 1968." (personal interview, 1998).

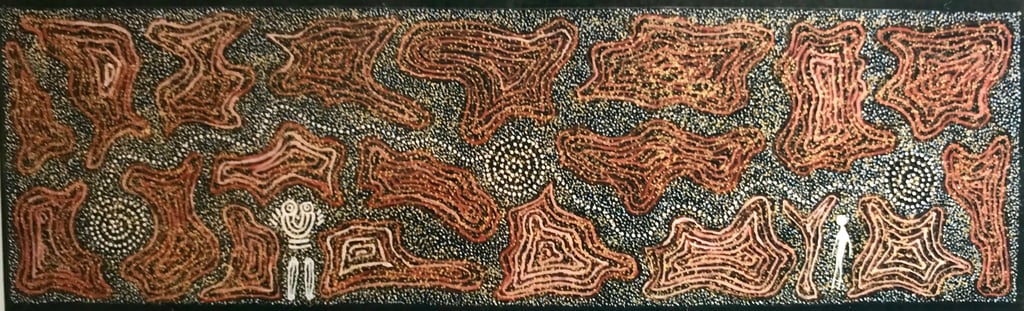

Barbara became an unwilling member of the Stolen Generation, and taken to institutions in Darwin and Brisbane. She was forbidden to speak her language and forced to work in places she described as being like jails. When she was finally able to leave, she searched for years for her family and was finally reunited in 1968. It took her many more years to relearn her native language, and had the honour of becoming the first woman and first ‘half-caste’ member of Utopia’s Urapuntja Council in 1984. During the 1980’s, Barbara began painting beautiful acrylic paintings, and her series ‘My Mother’s Country’ and ‘Grass Seeds’ have brought her international acclaim. She passed on her love of her country and her painting skills to all her children. When I was at Utopia with Barbara in 2000, we discovered that her mother Minnie who was about eighty-years-old was extremely ill. I persuaded Barbara to take her back to Adelaide with her to recuperate. While watching Barbara paint, Minnie asked for a brush and acrylic paint, and for the first time began to paint on canvas. They were based on body painting designs for her Bush Melon and Grass Seed Dreamings. The remarkable vitality and energy of her paintings celebrate and evoke the dynamic rhythms and movements of the awelye women’s ceremonies in exuberant colours. Strong, resolute women like Minnie and Barbara are the hope and proof of the strength and continuity of culture in the midst of the traumas that have beset it.

Change and adaptation have always been part of Aboriginal culture’s survival, and the challenges that the people face have never been greater. Throughout Australia in communities like Utopia, new traditions continue to emerge. What has remained constant is a connection to country that provides a unique role model of a different way of being in the world, one of grounded ecological custodianship. Their culture is to be celebrated and respected, and its paintings are heartfelt reminders of its strength and presence in Australia today.

Resilience and Relationship

Dr. Victoria King

Photograph of Barbara Weir and her mother Minnie Pwerle collecting the grass seeds of Minnie's Dreaming taken in 1999 by Victoria King.

Painting of 'My Mother's Country' by Barbara Weir in acrylic and ochre on canvas, 38 x 120 cm, 2000.

© Text and photograph copyright Dr. Victoria King 2026.